Taipei Medical University preparing to use brain imaging to “converse” with vegetative state patients

Source: College of Humanities and Social Sciences

Published on 2020-01-08

Over the past three years, the TMU Brain and Consciousness Research Center (BCRC) has evaluated nearly 150 patients, from all parts of Taiwan (including Kinmen), who suffer from Unresponsive Wakefulness Syndrome (UWS).

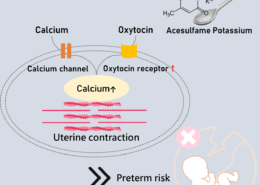

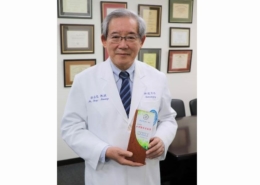

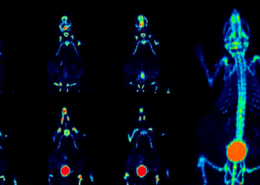

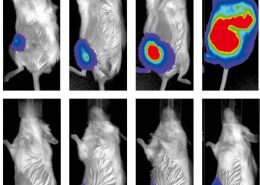

UWS is the condition that was formerly referred to as “vegetative state”: a disorder of consciousness in which patients seem to be neither conscious of self nor of the world around them. Of the patients who were evaluated, more than 65 have been admitted to a clinical trial that includes two types of neuroimaging, PET and fMRI, as well as the administration of the drug, Ambien. Ambien has the paradoxical effect of elevating levels of consciousness in some patients. TMU Prof. Timothy Joseph Lane, Dean of College of Humanities and Social Sciences, points out that 11 of the patients who have participated in the clinical trial have shown some signs of improvement.

Not only are some patients improving, but also previous research has shown that 40% of UWS patients are misdiagnosed: that is, they are actually, at least to some degree, aware of self and the external environment. Moreover, some neuroimaging evidence even suggests that as many as 20% of the patients, despite their inability to communicate in usual ways, may have levels of consciousness that are within the normal, healthy range.

Unfortunately, only in recent years, due to breakthroughs in neuroimaging research has neuroscience come to the full realization that, despite appearances, many patients who suffer from UWS know who they are and know what is happening to them. But they are trapped inside of bodies, unable to communicate their presence to anyone. Fortunately, now, it has become possible to engage these patients in direct communication, by asking them yes-no questions.

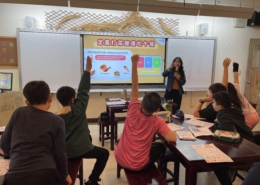

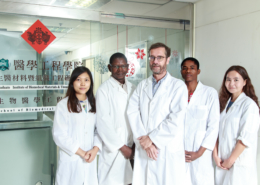

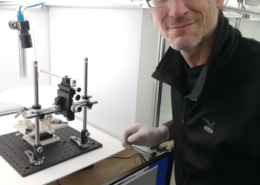

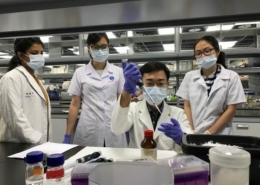

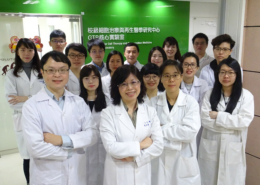

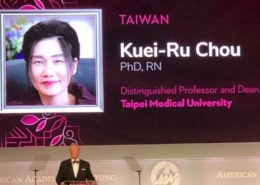

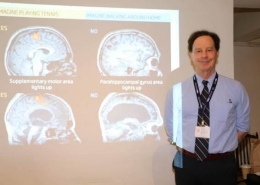

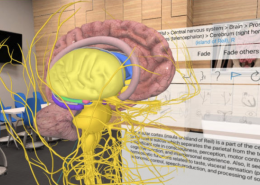

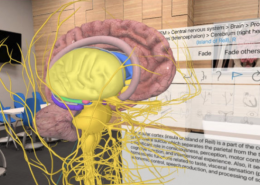

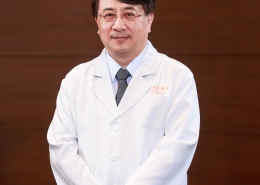

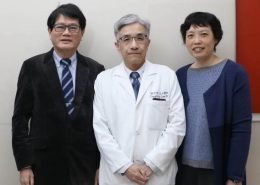

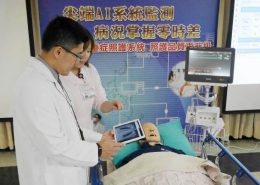

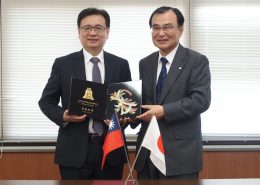

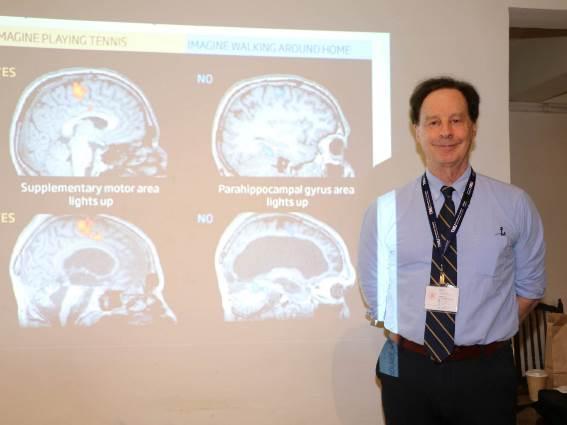

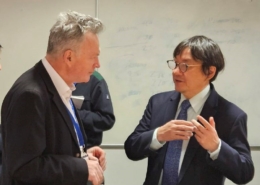

Picture: Prof. Timothy Joseph Lane observes that brain imaging technology, like PET and fMRI, when applied to UWS patients, can improve diagnoses, prognoses, and even provide the opportunity for direct communication.

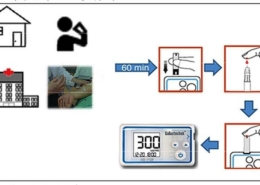

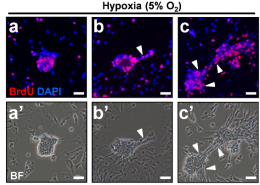

The key to this type of communication is that certain types of brain activity are fairly consistent from one person to another. For example, if you imagine swinging a tennis racket, and persist imagining for 30 seconds, fMRI can identify a distinctive pattern of activity in the supplementary motor area. Similarly, if you imagine walking around your home (spatial navigation), and persist for 30 seconds, fMRI can identify a distinctive pattern of activity in the parahippocampal gyrus. The breakthrough was the discovery that not only can healthy persons use imagination to evoke this activity, so too can approximately 20% of UWS patients!

Use of this approach makes it possible to ask yes-no questions of the patients. One begins by explaining to the patient that “imagine playing tennis” represents “yes”, and “imagine walking around your home” represents “no.” After patients have been given these instructions it is possible to ask any question that only requires a yes-no answer. Importantly, although it is not the case that each patient who can answer will recover a normal life, nevertheless, this method makes it possible to improve patient quality of life—we can learn about their likes, their dislikes, and we can restore to them the ability to make decisions for themselves. In this way we restore their sense of dignity.

Our research continues, but the cost of PET and fMRI scanning, when combined, is nearly 40,000. And this price is only sufficient to cover a short period of time. If, as we hope, we can continue the clinical trial, while also beginning to communicate with patients, we’ll require more funding than is typically available through government agencies. Naturally, too, families of limited economic means cannot afford the cost of arranging to communicate with their family members, while the patients recline inside the scanner. For this reason we hope to secure donations, both to continue the clinical trial and to create opportunities to improve patient quality of life.

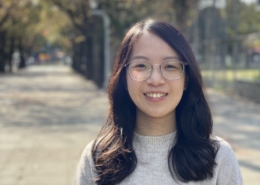

Ms. Zheng (鄭) has taken care of her mother, who suffers from UWS, for over two years. She says that sometimes her mother will turn her head slightly or blink her eyes; Ms. Zheng says her family deeply hopes that they will have the chance to interact with their mother. Ms. Zheng is only one of many who take care of family members afflicted with UWS. They all want to know what the patients are feeling, whether they experience discomfort. What is more, through direct communication, they can learn more about simple pleasures, preferences in music or food. Of yet more importance, autonomy can be returned to patients, including whether patients wish to continue, or discontinue, care. We already know that many patients are misdiagnosed and that, of these, some are fully conscious; we also know how to communicate with them. In a word, we have in our hands the opportunity to release these patients from the bodies that imprison them.

-260x185.jpg)

與連江縣衛生福利局陳美金局長簽署醫療合作備忘錄-260x185.jpg)

期許永續發展成為醫療產業新契機。-260x185.jpg)